- Home

- Pollinators

Pollinators in the Vegetable Garden

Monarch Butterfly:

Monarch Butterfly:The Iconic Pollinator

The global decline of pollinators has been making news lately. But when I was a kid, the now-iconic monarch butterfly was so common that it was about as exciting as a pigeon would be to a birdwatcher.

Sadly, monarchs have now become the poster child for the decline of pollinators around the world.

So last summer, when I saw my first monarch in twenty years, I ran inside shouting "Tito! There's a monarch on the milkweed!" She was laying single eggs on the undersides of several leaves, which I gleefully checked daily with a 32-power hand lens. Then I duct-taped the hand lens over my iPhone and took a bunch of pictures of the tiny green caterpillars that hatched.

What's happening with pollinators is a fascinating and important story, so I have broken the topic up into these three links:

What Are Pollinators, and Why Are They Important?

Newly-Hatched

Newly-HatchedMonarch Caterpillar

A pollinator is any living thing (often an insect, bird, or bat) that transfers pollen from the male "anther" of a flower to the female "stigma". Pollination is required in order for the plant to make viable seeds. Some plants are pollinated by wind, but the term "pollinator" refers only to living things that pollinate flowers.

Most fruits, vegetables, leafy greens, nuts and beef (because most cows eat alfalfa) depend on pollination for their existence. According to the USDA: "Some scientists estimate that one out of every three bites of food we eat exists because of animal pollinators like bees, butterflies, moths, birds, bats, beetles and other insects."1

Domestic Honeybee Pollinating a Borage Flower in My Vegetable Garden

Domestic Honeybee Pollinating a Borage Flower in My Vegetable GardenPollinators, however, are crucially important for much more than just

the food we eat. All plants - not just food ones - are important pieces

of ecosystems that make up the intricate web of life that

is all tied together. And we are a part of it, not apart from it.

Pollinators, too,

are part of food chains that support whole ecosystems. Ecosystems involve webs of interacting processes, intricately balanced by nature

(or God, depending on your belief) to function as one integrated

whole. We can think of them as living, breathing, 3D jigsaw puzzles.

When I was growing up we always had a jigsaw puzzle set up on a card table in the living room. Unbeknownst to us, a visiting friend once took a few pieces of the puzzle and hid them. We didn't realize anything was wrong until late in the game, when we searched and searched but couldn't find the pieces we needed to fit the spaces.

A Painted Lady Butterfly and a Bumblebee on an Echinacea Flower

A Painted Lady Butterfly and a Bumblebee on an Echinacea FlowerUnlike our puzzle pieces that were eventually returned,

we're now losing pollinator species, and when they are

gone, it's forever. If ecosystems lose enough critical pieces (processes) of the

puzzle, they may collapse and perish.

For some

pollinators, it's late in the game now, and scientists are waving red

flags warning us that some pieces are already missing and

others are dangerously scarce. Pollinators are critical in animating the web of life upon which human

life itself depends.

How Can I Help Pollinators?

"Man, that's heavy!" as we said in the 60's... But here's the alternate prospect:

As vegetable gardeners (or even larger-scale farmer/ranchers) we have the power to restore our land, however small, to its natural, ecologically-sound, sustainable, healthy state.

And small actions taken by many people become big actions. As one of my teachers, Dan Kittredge, says of regenerative agriculture: "If it's true it will work, if it works it will spread".

It is true, it does work, and it is spreading. You can help, both by caring for your soil and garden using the methods explained on this website, and by joining our tribe, which cares for the soil, grows food that nourishes, and loves the whole web of life.

Showy Milkweed is as Loved by Pollinators as It is Despised by My Neighbors. (Guess Who Won?)

Showy Milkweed is as Loved by Pollinators as It is Despised by My Neighbors. (Guess Who Won?)1) Plant native flowering plants.

We

can interplant native flowering plants among or around our vegetables

to attract and feed both native and agricultural honey bees. Plant as

many different varieties as you can, and try to have something in bloom

from early spring to late fall. If you can, plant milkweed for monarchs.

Wild showy milkweed is their favorite food and also where they lay

their eggs, which eat the milkweed leaves when they hatch.

To

find good choices for plants that will support native pollinators in

your area, you can check with your State University Extension Service

(in the US) or a good local nursery. There are also excellent regional

guides available on The Xerces Society website, which also has links to international sources.

While you're at it, you might consider joining The Xerces Society, whose mission is "to protect the natural world by conserving invertebrates and their habitat". Their work involves research, education, and outreach to help pollinators worldwide, and offer several excellent books, as well as a "Pollinator Habitat" sign for your garden, to help fund their work.

Metallic Green Sweat Bee on a Cosmos Flower

Metallic Green Sweat Bee on a Cosmos Flower2) Plant regular garden-variety flowers that feed pollinators.

Besides

native perennial wildflowers to feed native bees, some great "garden-variety" flower

choices that many pollinators love are cosmos, bee balm, lavender, marigolds,

butterfly bush, hummingbird mint, salvia, hyssop, coreopsis, zinnias, calendula,

sunflowers, yarrow, scabiosa, verbena, borage, culinary herbs

(sage, oregano, basil, thyme), liatris, penstemons, asters, asclepias

and bachelor's buttons.

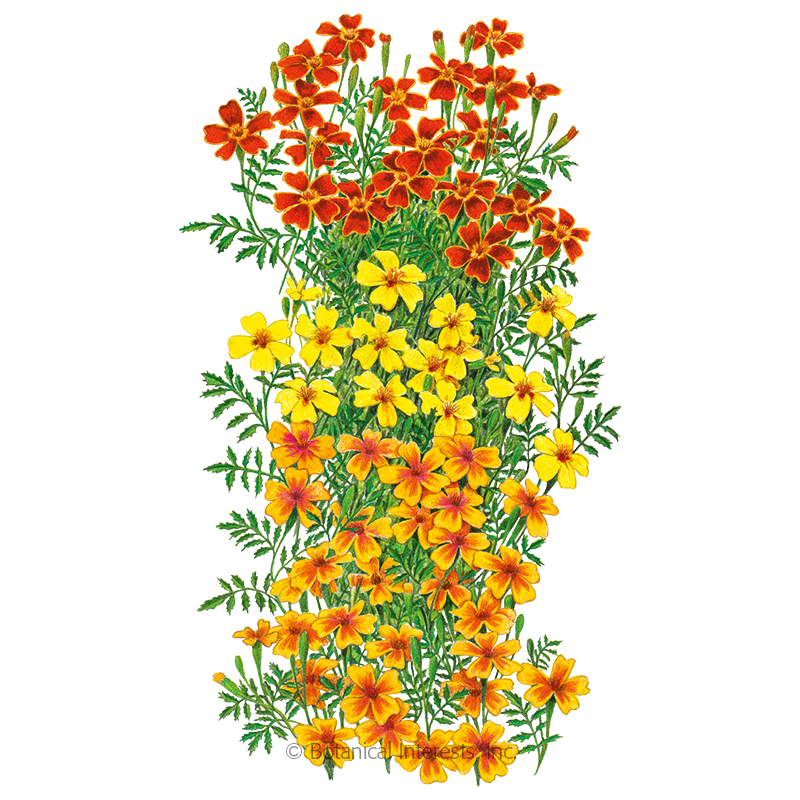

Choose "single" varieties like the French marigold pictured below. The fancy "double" flowers that breeders have developed to please the eye do not feed pollinators because their nectar is inaccessible.

Botanical Interests Seeds offers many flowers that attract pollinators, including some excellent blends. Last time I checked they had more than 200 varieties of pollinator-friendly flowers!

I have a more comprehensive article on this at: How to Attract Bees

Hunt's Bumblebee on a French Marigold

Hunt's Bumblebee on a French Marigold3) Do not use pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides.

If you are

still using pesticides, learn and implement the principles of soil

health to bring your soil, and hence your plants, back into vibrant

health. A vibrantly healthy plant does not taste good to pests, who,

like wolves hunting elk, prey on the weakest members. Healthy plants

naturally resist pests, just as healthy people have greater resistance

to colds. (An article on the principles of soil health is coming soon.)

4) Provide nesting places for wild pollinators.

Honeybees will fly back to their hives at dusk. But solitary and communal native bee species need places to shelter and lay eggs. We can provide them habitat by leaving a brush pile in the corner of the garden, leaving some bare, undisturbed ground completely alone (this one is important), and building or buying habitat houses. Crown Bees offers some great choices, YouTubes abound on how to build and manage mason bee habitats. We tie up the fine prunings from our peach and apple trees in tight bundles, and leave them at the back of the firewood pile undisturbed for a year. We've found sphinx moth chrysalis' there. Bundles of old raspberry canes or sections of lake bed reeds (phragmites) are also good choices

5) Provide water.

Many insects drown

while trying to drink water from sources that are too deep for them,

like birdbaths or pools (sadly, our duck pool). They also need a bit of

salt, which is precisely why bees sometimes hang out around the edges of

a swimming pool. As the splashed water starts to evaporate, the

dissolved minerals in it become concentrated, so the bees can easily lap

it up. We can mimic this by providing a shallow dish of water with

stones in it. I keep ours near the hose bib, and occasionally I add a

dash of Himalayan salt to the water to provide both sodium chloride and

many trace elements.

Pollinator Drinking Party

Pollinator Drinking Party6) Support regenerative agriculture, and implement its practices.

Regenerative agriculture is slowly "taking root" across the nation and around the world as a viable, long-term solution to the Use regenerative practices on whatever scale you can, and buy food from regenerative farms and ranches.

Regenerative agriculture, properly executed, outperforms the status quo of industrial agriculture while benefiting soil, pollinators, wildlife, livestock, people, ecosystems and the farmers' bottom line.

An excellent introduction to what regenerative agriculture is and what it can do is the book Dirt to Soil by Gabe Brown. You can also support the necessary changes unfolding on farms across the country by buying food from farmers listed on the Regeneration International

I live in the high plains at the base of the Rocky Mountains, and I grow

gaillardia, echinacea, a variety of penstemons, monarda, native

sunflowers, rudbeckia, showy milkweed and dandelions. (My neighbors

especially love me for these last two.) Some of these flowers are

interplanted in my vegetable beds, but I also have two dedicated

pollinator gardens nearby, which is where the photos on this site were taken. There is a bit more info over at How to Attract Bees.

References

1) https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national/plantsanimals/pollinate/)

Help share the skills and spread the joy

of organic, nutrient-dense vegetable gardening, and please...

~ Like us on Facebook ~

Thank you... and have fun in your garden!

Affiliate Disclaimer

This website contains affiliate links to a few quality products I can genuinely recommend. I am here to serve you, not to sell you, and I do not write reviews for income or recommend anything I would not use myself. If you make a purchase using an affiliate link here, I may earn a commission but this will not affect your price. My participation in these programs allows me to earn money that helps support this site. If you have comments, questions or concerns about the affiliate or advertising programs, please Contact Me.Contact Us Page